New Values and Old Orders: Where do North Koreans Fit in the New South Korea?

New Values and Old Orders: Where do North Koreans Fit in the New South Korea?

Since 1998, the number of migrants in South Korea has increased nearly tenfold, a small part of whom are North Korean defector-migrants. In part, this increase was caused by the relatively open immigration regime put in place to deal with South Korea’s low birth rate, but now it is causing demographic change: South Korea is very different today than it was twenty, thirty years ago. So who do South Koreans prefer as newcomers in their society? Where do North Koreans fit in, and how are they integrating socially and politically? These were the questions put forward on the 16th of May 2019, when Steven Denney and Christopher Green presented their research: “New Values and Old Orders: Where do North Koreans Fit in the New South Korea?”

The presentation was given by Steven Denney, who explained their research design: first, they put South Korean respondents in the shoes of an immigration officer, who would have to select one of two (imaginative and randomly generated) applicants on the basis of their reason for application, country of origin, Korean language capacity, occupation, employment plans, gender and ethnicity. This design allowed them to highlight which characteristics are deemed the most desirable for migrants coming to South Korea. The outcomes of this experiment demonstrated that the reason for applying was not very relevant, though there was origins-based discrimination: migrants from the United States were most welcomed, followed by North Korean defector-migrants. Most importantly, language skills matter tremendously and the greatest effect was seen with employment plans. In other words, whether you plan to get a job upon arrival in South Korea is the most important factor. To give an example, a North Korean male migrant with no plans to work would have a 62% chance of being selected, whereas a female North Korean migrant with plans to look for work had a 75% chance: it is all about your ability and willingness to contribute to South Korean society.

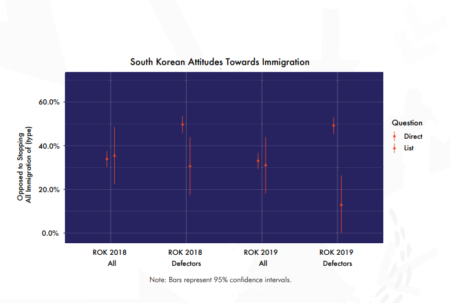

Second, Steven Denney introduced a potential issue: in surveys like this, people might give socially desirable answers that are in line with what the group might expect. Therefore, they designed a second experiment which would give the respondents “plausible deniability”, i.e. that their exact individual preferences are obscured. Then, from this experiment the researchers inferred whether the respondents opposed stopping immigration of North Koreans, and compared the results with the results of surveys where respondents were asked this question directly. In case the respondents were asked directly, about 50% opposed stopping migration from North Korea, whereas in their experiment, this dropped to only 15%. Put in simpler terms: there is concrete evidence that in regular surveys on this topic, South Korean respondents give highly socially desirable answers that do not represent their personal preferences.

As the third and final part of the presentation, the researchers also surveyed North Korean migrants in South Korea themselves. Based on the survey, these migrants actually prefer a more ethnically homogeneous South Korea, whereas native-born South Korea are more in favour of multiculturalism. At the same time, North Korean defector-migrants actually show slightly greater support for the South Korean democracy than South Koreans do themselves.

After the presentation, there was a discussion by Michael Meffert and Remco Breuker (both Leiden University). Dr. Meffert lauded the state-of-the-art experimental methods used by the researchers, but stated that there was lots of complexity and uncertainty. For instance, do South Korean citizens really have a “true opinion” when it comes to such complex issues? His suspicion was that there is a high level of ambivalence in their opinions, which means that the respondents also do not demonstrate such a clear opinion in the first place.

Following Dr. Meffert’s remarks, Prof. Breuker also commented on the presentation. He first questioned what the term “multiculturalism” really meant. For many, it seems a rather meaningless or ambiguous term. Second, Breuker wondered what would happen if the question about the immigration officer was framed differently. His argument was that if you put someone in the shoes of an immigration officer like in this research, their personal preferences might not shine through as they pretend to represent the public. These are all questions that the researchers might address in their further research.

Interested in the full outcomes of the research? The full research report is publicly available and can be downloaded here.

New Values and Old Orders: Where do North Koreans Fit in the New South Korea?

Since 1998, the number of migrants in South Korea has increased nearly tenfold, a small part of whom are North Korean defector-migrants. In part, this increase was caused by the relatively open immigration regime put in place to deal with South Korea’s low birth rate, but now it is causing demographic change: South Korea is very different today than it was twenty, thirty years ago. So who do South Koreans prefer as newcomers in their society? Where do North Koreans fit in, and how are they integrating socially and politically? These were the questions put forward on the 16th of May 2019, when Steven Denney and Christopher Green presented their research: “New Values and Old Orders: Where do North Koreans Fit in the New South Korea?”

The presentation was given by Steven Denney, who explained their research design: first, they put South Korean respondents in the shoes of an immigration officer, who would have to select one of two (imaginative and randomly generated) applicants on the basis of their reason for application, country of origin, Korean language capacity, occupation, employment plans, gender and ethnicity. This design allowed them to highlight which characteristics are deemed the most desirable for migrants coming to South Korea. The outcomes of this experiment demonstrated that the reason for applying was not very relevant, though there was origins-based discrimination: migrants from the United States were most welcomed, followed by North Korean defector-migrants. Most importantly, language skills matter tremendously and the greatest effect was seen with employment plans. In other words, whether you plan to get a job upon arrival in South Korea is the most important factor. To give an example, a North Korean male migrant with no plans to work would have a 62% chance of being selected, whereas a female North Korean migrant with plans to look for work had a 75% chance: it is all about your ability and willingness to contribute to South Korean society.

Second, Steven Denney introduced a potential issue: in surveys like this, people might give socially desirable answers that are in line with what the group might expect. Therefore, they designed a second experiment which would give the respondents “plausible deniability”, i.e. that their exact individual preferences are obscured. Then, from this experiment the researchers inferred whether the respondents opposed stopping immigration of North Koreans, and compared the results with the results of surveys where respondents were asked this question directly. In case the respondents were asked directly, about 50% opposed stopping migration from North Korea, whereas in their experiment, this dropped to only 15%. Put in simpler terms: there is concrete evidence that in regular surveys on this topic, South Korean respondents give highly socially desirable answers that do not represent their personal preferences.

As the third and final part of the presentation, the researchers also surveyed North Korean migrants in South Korea themselves. Based on the survey, these migrants actually prefer a more ethnically homogeneous South Korea, whereas native-born South Korea are more in favour of multiculturalism. At the same time, North Korean defector-migrants actually show slightly greater support for the South Korean democracy than South Koreans do themselves.

After the presentation, there was a discussion by Michael Meffert and Remco Breuker (both Leiden University). Dr. Meffert lauded the state-of-the-art experimental methods used by the researchers, but stated that there was lots of complexity and uncertainty. For instance, do South Korean citizens really have a “true opinion” when it comes to such complex issues? His suspicion was that there is a high level of ambivalence in their opinions, which means that the respondents also do not demonstrate such a clear opinion in the first place.

Following Dr. Meffert’s remarks, Prof. Breuker also commented on the presentation. He first questioned what the term “multiculturalism” really meant. For many, it seems a rather meaningless or ambiguous term. Second, Breuker wondered what would happen if the question about the immigration officer was framed differently. His argument was that if you put someone in the shoes of an immigration officer like in this research, their personal preferences might not shine through as they pretend to represent the public. These are all questions that the researchers might address in their further research.

Interested in the full outcomes of the research? The full research report is publicly available and can be downloaded here.