LAC Shorts: The Russia-Ukraine War in the Chinese Media

Recent themes surrounding the Russia-Ukraine conflict in Chinese online media show how the war is framed by news outlets and bloggers when it comes to China’s role in it, shifting the narrative from Beijing’s responsibility to Washington’s irresponsibility.

By Manya Koetse

As the Russian-Ukraine conflict shows no signs of de-escalation and over two million people have now fled Ukraine, there is a heightened international media focus on Chinese responses to the war.

While the developments in Ukraine are a major topic in Chinese newspapers, on its social media sites, and in its press briefings, the Russia-Ukrainian war – which is commonly referred to as Russia’s “special military operation” – is placed within a specific Chinese narrative.

Within that news narrative, emphasis is placed on the role of the United States, its Western allies, and Chinese resistance against the ‘Cold War mentality’ that allegedly fueled the current crisis. Some themes are recurring in the Chinese media, where today’s violent conflict in Ukraine is also used to reflect on the past and future of China-West relations. In light of the recent developments, NATO’s bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade (1999) became a topic of focus again, together with discussions on what the Ukraine war could mean for Taiwan. In this article, we will explore some of the trends dominating Chinese media discussions within the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“NATO Owes Blood Debt to China”

On February 24th, when people around the world were closely following the latest developments of Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine, two hashtags went trending on Chinese social media: “The NATO Still Owes Blood Debt to China” (#北约至今还欠中国一笔血债#) and “The US is Not Qualified to Tell China How to Act” (#美方没资格来告诉中方怎么做#).

These hashtags were promoted on Sina Weibo, one of China’s biggest social media platforms, by state media outlet People’s Daily, receiving over 1.2 billion and 650 million views respectively.

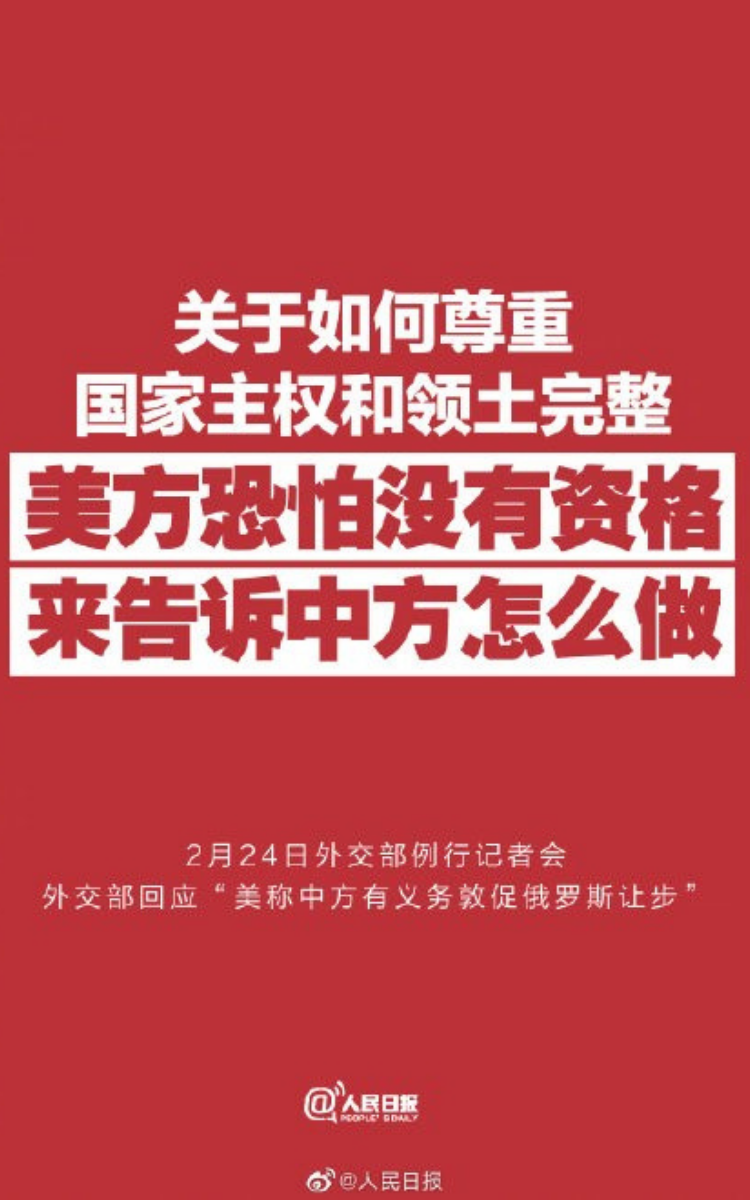

Online poster published by People’s Daily reiterating the words of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson that the United States is not qualified to tell the Chinese side on how to act in light of national sovereignty and territorial integrity (source: People’s Daily, Weibo).

Online poster published by People’s Daily reiterating the words of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson that the United States is not qualified to tell the Chinese side on how to act in light of national sovereignty and territorial integrity (source: People’s Daily, Weibo).

The sentences came up during the February 24th press conference of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which spokesperson Hua Chunying answered various questions relating to the situation in Ukraine. One of them, posed by a CCTV reporter, referred to comments made by US State Department spokesperson Ned Price, who suggested that China has an obligation to urge Russia to “back down” to de-escalate the situation.

Hua Chunying responded by mentioning China’s recent history of humiliation at the hands of Western powers, saying that “the US is in no position to tell China off.” Hua brought up the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia, which killed three Chinese journalists, stating: “NATO still owes the Chinese people a debt of blood.”

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson condemned the United States for its history of continuous overseas military operations and claimed that China still faces “a realistic threat” from the U.S. and its allies today. Joining Western ‘bloc politics’ in condemning Russia is not something China is interested in doing, she concluded. One video of Hua Chunying’s remarks received over two million ‘likes’ on the Weibo platform.

How this specific moment of the press conference was singled out and highlighted by Chinese state media set the tone for the way in which the Russia-Ukraine conflict is framed by official media when it comes to China’s role in it, shifting the narrative from Beijing’s responsibility to Washington’s irresponsibility.

The China Daily frontpage of February 24th literally mentioned how the “irresponsible” United States was “adding fuel to the Ukraine crisis” and accused Washington of aggravating tensions and creating panic on the Ukraine issue. The Jiefang Daily reiterated that same message, meanwhile stressing that China has acted as a responsible leader in avoiding incitement of war (Mo 2022, 1; Liao Qin 2022, 5).

Cartoon published on the English-language site of Chinese state-run media outlet Global Times, by Global Times cartoonist Liu Rui (source link).

Cartoon published on the English-language site of Chinese state-run media outlet Global Times, by Global Times cartoonist Liu Rui (source link).

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, videos showing footage of the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade started circulating online. The influential online news portal Guancha.cn was one of the accounts sharing a short video showing footage of the aftermath of the deadly bombing by the U.S. government, which claimed its intention had been to bomb a Yugoslav arms agency (Parsons & Xu 2001: 51). “We can never forget this day,” Guancha.cn wrote, and soon there were bloggers creating new content on the Belgrade incident explaining why the NATO owed the Chinese people and why the U.S. has no right to pressure China in how to act.

Screenshots from online info sheets explaining “What is NATO’s blood debt to China?” by well-known comic blogger @赛雷三分钟 (link to Weibo source).

Screenshots from online info sheets explaining “What is NATO’s blood debt to China?” by well-known comic blogger @赛雷三分钟 (link to Weibo source).

This trending topic is telling for how the Russia-Ukraine conflict comes up in Chinese news coverage and on Chinese social media, with many reports and discussions about the situation actually not focusing on what is happening on the ground in Ukraine, but instead focusing on other issues that are framed within Chinese news narratives of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The NATO bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia is one example. The status of Taiwan is another larger recurring topic discussed within the context of the Ukraine conflict.

“Today’s Ukraine, Tomorrow’s Taiwan?”

Soon after the Russian invasion of Ukraine became a reality, Chinese social media users began drawing comparisons between the Taiwan situation and the Ukrainian developments.

“Today’s Ukraine, tomorrow’s Taiwan?” is a phrase that is going around Chinese media a lot these days. On the one hand, many online commenters see the rapid invasion of Ukraine as a warning to Taiwanese that the situation in Taiwan could change within a time frame of just a few days. One meme making its rounds showed a pig called “Taiwan” watching another pig, “Ukraine”, get slaughtered.

A meme circulating on social media shows a pig “Taiwan” watching the slaughtering of another pig “Ukraine.”

Other bloggers see the developments in Ukraine as a warning to mainland Chinese that the West could influence and trigger conflict, and that they could send weapons or provide military support to Taiwan if mainland China would employ force to realize a ‘reunification’ with Taiwan.

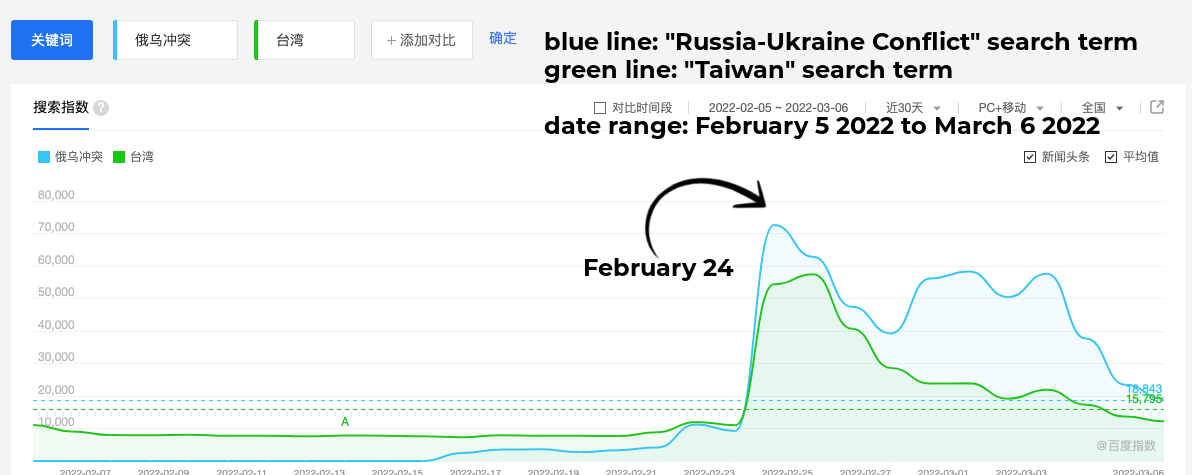

Although Chinese authorities have stated that it would be unwise to draw parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan, online conversations comparing the two are ongoing. The search index of Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, clearly shows how web search queries for ‘Taiwan’ peaked at the same time when searches for the term ‘Russia-Ukraine Conflict’ also exploded (see image below).

Baidu Index trend search tool, screenshot via author.

Baidu Index trend search tool, screenshot via author.

This trend is also fueled by Chinese state media reports about Taiwan. On February 26th, the Global Times news outlet reported that the US Navy destroyer Ralph Johnson was passing through the sensitive Taiwan Strait. Although American officials called the passage “routine” (the warship also sailed through the Taiwan Strait in previous years), the move was presented as a provocative one by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs during a press conference on March 1st.

Following more discussions on Taiwan in the light of Ukraine developments, China Central Television News (CCTV) initiated the hashtag “The Hope for Taiwan’s Future Lies in Achieving National Reunification” (#台湾的前途希望在于实现国家统一#) after Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi addressed the issue during a March 7 press conference.

Although the Ministry of Foreign Affairs once again stressed how Ukraine and Taiwan could not be compared because of Taiwan’s status as “an inalienable part of China’s territory” that will eventually be reunified with the mainland, the address inescapably added to the incorporation of the Ukraine issue into a specific Chinese narrative, triggering more discussions on the differences and similarities between Ukraine’s today and Taiwan’s tomorrow.

“If You’re Anti-War, You Must Be Anti-American”

One other trend that has been clearly visible in Chinese social media discussions regarding the Ukraine conflict is the perceived dichotomy between being ‘anti-war’ and ‘anti-American.’

Although there certainly is public sympathy for the victims of this conflict, Chinese social media is seeing a growing trend of people opposing the anti-war movement, calling them hypocritical and naive for raising their voices to call out this war while they perhaps were not as vocal in condemning other conflicts. According to this reasoning, strong anti-war opponents are labeled as being ‘pro-American.’

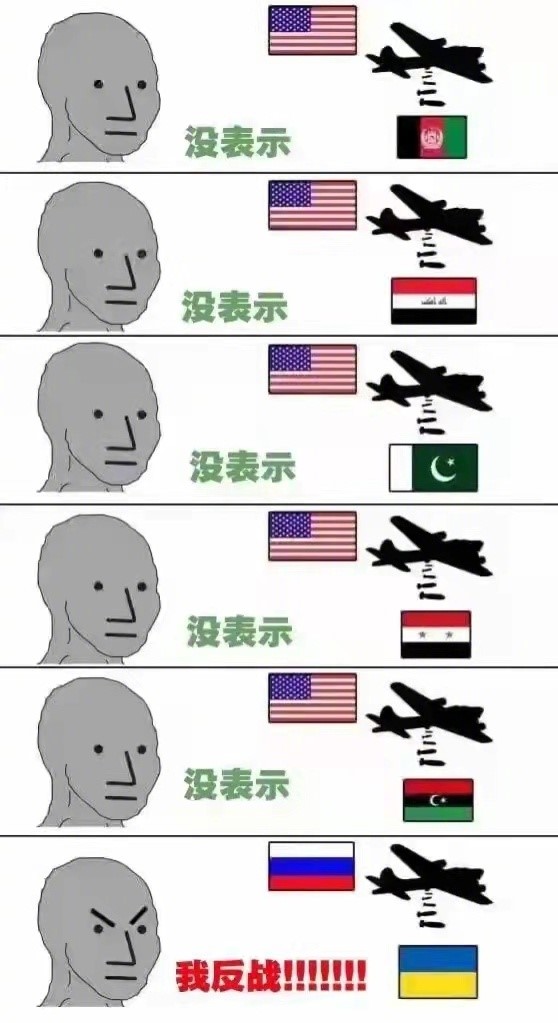

One popular science blogger (12+ million followers) on Weibo nicknamed Occam’s Razor (@奥卡姆剃刀) posted a meme (image below) on February 27th, writing:

“Some people are bitterly bashing Russia while self-righteously preaching against the war. Of course, it is correct to be anti-war, and everyone should defend world peace. But you should ask them: were you also anti-war when the United States invaded Iran, Iraq, Panama, Libya, Yugoslavia, or Afghanistan?”

One meme shared on social media, showing a person with “no expression” when the U.S. drops bombs on Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria, Libya, and shouting “I’m Anti-War!!” in the last picture when Russia attacks Ukraine.

The idea that anti-war advocates have a hidden agenda if they are not also speaking out against the United States is visible in countless of posts and videos, not just on Chinese social media site Weibo but also on other popular platforms such as Bilibili and Douyin, where catchy slogans such as “If you’re anti-war but not anti-American, you’re up to no good [you have ulterior motives]” (“反战不反美,心里都有鬼”) and “If you’re anti-war and not anti-American, you are inhumane” (“反战不反美就是反人类”) are ubiquitous.

Over the past years, China’s online media environment has seen several waves of anti-Americanism. In the fall of 2021, China’s epic war movie The Battle at Lake Changjin became a major success. The film, that shows how Chinese troops were severely underestimated by the U.N. forces during the Korean war, came at a time of heightened U.S.-China tensions. According to one of the scriptwriters, the film was supposed to convey that “the Chinese are not to be messed with” (Koetse 2021). It sent out the message that China had to enter the war to fight the ‘imperialist’ United States and its allies as these foreign forces, who looked down on them, would otherwise expand all the way to the doorstep of China and endanger the peaceful development of their newly established nation.

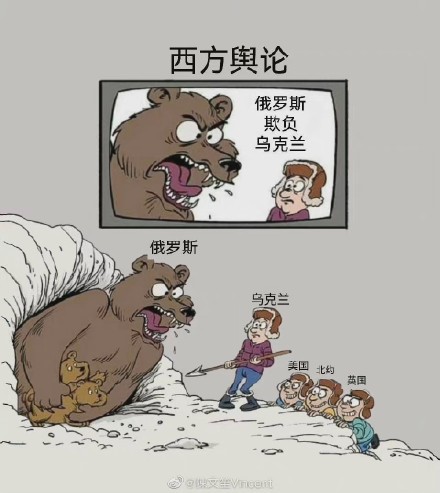

Many Chinese are now also suggesting that the Ukraine conflict is like “China’s Korean War for Russia.” One political cartoon shared on social media titled “Western Public Opinion” shows a zoomed-in image of a big scary bear (“Russia”) and a small, frightened man (“Ukraine”) on a television screen. The scene below shows the full scene, revealing how the small “Ukraine” man, backed by three helpers (“U.S.”, “NATO,” and “Britain”), is poking at the mother bear (“Russia”) who is protecting her cubs in her den.

This adapted cartoon was shared on Weibo, original cartoon is by Pusang Gala and is titled “Narrative vs Reality” (artist page on Facebook).

Online anti-American sentiments are also fueled by Chinese media reports highlighting how other Asian countries supposedly criticize the West and support Russia. When Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan lashed out in response to foreign pressure pushing Pakistan to condemn Russia – asking “What do you think of us? Are we your slaves?” – Chinese media outlet Guancha.cn was quick to turn the topic into a social media hashtag (“Pakistan Asks: Are We a Slave to the West?”). Similarly, the state-run Global Times promoted one of its articles about Indian social media users showing their support for Putin (hashtag: “Great Number of Indian Web Users Strongly Support Russia”).

Meanwhile, the English-language Global Times Twitter account posted a photo of India allegedly lighting up one of its landmark buildings, the Qutub Minar, in support of Russia. The tweet turned out to be misleading, as the Qutub Minar was illuminated on the occasion of Jan Aushadhi Diwas to generate awareness about the usages of generic medicines.

Tweet by Global Times, screenshot by author.

Tweet by Global Times, screenshot by author.

On March 8, as the war between Russia and Ukraine entered day 13, one of the top trending topics on Chinese social media was not the two million people who have fled the war, but the alleged uncovering of 26 U.S. military biological laboratories in Ukraine (hashtag: “The 26 American Biolabs in Ukraine Are Just Tip of Iceberg”).

During a press briefing, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Zhao Lijian expressed concern over the alleged existence of many U.S. biological labs in Ukraine and elsewhere, and questioned the intentions behind running them. According to Bloomberg News, the Chinese accusations of the American military operating ‘dangerous’ biolabs mirrored Russian diversion tactics to justify the Russian invasion. But on Weibo, the topic was viewed over 180 million times within hours and led to countless of comments from Chinese web users condemning the U.S. and demanding answers about the truth behind these biological laboratories.

The Russia-Ukraine war is dominating Chinese online media, without zooming in on what exactly is taking place on the battlegrounds today. In the end, the main framework that Chinese media outlets and bloggers are using to make sense of the Russia-Ukrainian conflict might have much more to do with Beijing’s own strategic ambitions in a changing international community than it has to do with Moscow or Kyiv. Strengthening that news frame is the narrative of China’s painful memories of humiliation at the hands of the very same Western powers that are now trying to get China on their side.

References*

Koetse, Manya. 2021. “The Unforgotten Victory: Why ‘The Battle at Lake Changjin’ Is One of China’s Biggest Films Yet.” What’s on Weibo, November 4 https://www.whatsonweibo.com/the-unforgotten-victory-why-the-battle-at-lake -changjin-is-one-of-chinas-biggest-films-yet/ [7.3.22].

Liao Qin. 2022. “The Impact of the Russian-Ukrainian Conflict on World Patterns [俄乌冲突 对世界格局影响几何].” (In Chinese). Jiefang Daily, February 25: page 5.

Mo Jingxi. 2022. “US adding fuel to Ukraine crisis ‘irresponsible.’” China Daily Hong Kong, February 24: page 1.

Parsons, Paul and Xu Xiaoge. 2001. “New Framing of the Chinese Embassy Bombing by the People’s Daily and the New York Times.” Asian Journal of Communication 11 (1): 51- 67.

*All other sources are linked to within the text, both in Chinese and English language.

About the author

Manya Koetse is a Sinologist and Japanologist (MPhil, Leiden University) and the editor-in-chief of What’s on Weibo, a news site that provides insights into Chinese social trends and online media.